by the Latin America Bureau (LAB)

In Latin America, a new generation has come of age over the last twenty years or so. This is a generation which has grown up in a period of relative prosperity in what has historically been one of the world’s poorest regions. It is a generation better educated and better informed than those which came before it. With access to modern communications technology, it is also better connected, more global and more outward looking. And with little or no direct memory of dictatorship, it is also a generation with less fear. But this new consciousness is not exclusive to the young: Latin Americans of all ages today are better equipped to analyse, discuss and combat the problems affecting their societies than ever before, and are doing so in a vast number of ways which are surprising, innovative and inspiring. What is more, they have achieved significant successes, often against the most improbable odds. Hence Latin America Bureau’s forthcoming title, Voices of Latin America. We aim to provide an account of this uncertain, fractious and yet exciting time, through the voices of people on the ground who are trying to make a difference in their communities and in their countries.

Such voices include Eva Sanchez, from the department of Intibuca, Honduras. Intibuca is Honduras’ poorest department and has the country’s highest alcoholism rate, as well as some of the worst rates of violence against women in what is one of the most dangerous countries in the world. Eva is director of Las Hormigas, an organisation which defends women’s rights and campaigns against gender-based violence. For Eva, violence against women has become “much worse” since the 2009 coup which deposed the legitimate president Manuel Zelaya. “There were many good laws before the coup that have since regressed—laws in general, not just dealing with women,” she says. “The penal code that they are working on now will result in severe human rights violations, restricting political participation and making it harder for women to defend their rights.” Nonetheless, she remains optimistic: “What we are doing here is the work of the ant [la hormiga]: it might be a small, insignificant animal, but they can carry great burdens and working together they achieve a lot.”

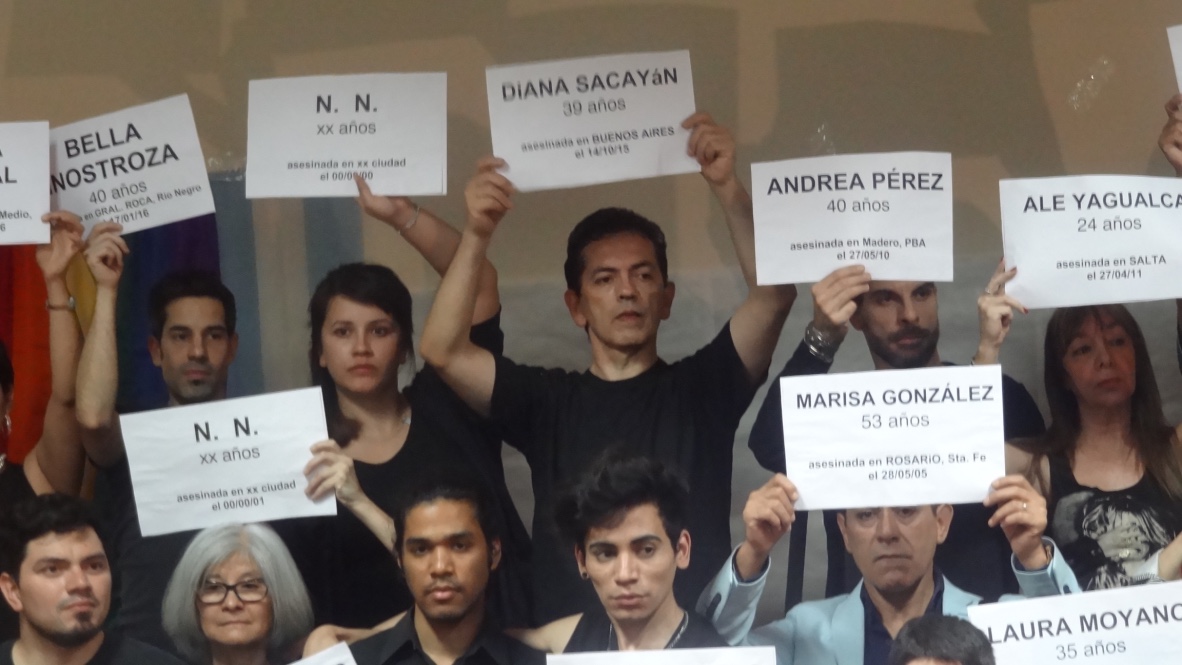

Another of these voices is Edgardo Fernandez, an Argentine LGBT activist and tango teacher. Edgardo dances queer tango which, in his words, “is a different way of teaching, learning, dancing and behaving in the realm of tango.” Unlike in traditional tango, where women are not permitted to ask men to dance, in queer tango, women may ask men to dance and of course, same-sex pairs are possible. “When we teach tango,” he explains, “we never talk about men or women. We talk about the “Lead” and the “Follow”. We never say that the roles are fixed, but that they can change. We also never say that anyone should obey what the other person does, but that both should make suggestions.” Edgardo uses tango events and flash mobs as a form of social and political protest, not just on LGBT issues, but also against gender-based violence and the neglect and mistreatment of the elderly. Having been active in gay rights organisations for 34 years, he has helped bring radical change to Argentina. Throughout the 1980s the LGBT community was routinely harassed by the police; today, Argentina has some of the most advanced LGBT rights in the world. “I think in the current social and political context,” he says, “there’s no going back.”

Constanza San Juan Standen and Stefanía Vega (Coordinación de Territorios en Defensa de los Glaciares, Chile)

Many of these voices come from communities which have been adversely affected by Latin America’s current economic model, which is based heavily on massive extraction of commodities such as soybeans, minerals and fossil fuels. Constanza San Juan Standen and Stefanía Vega, from the group Coordinación de Territorios en Defensa de los Glaciares, have been fighting a proposed glaciers law in Chile, which is home to 82% of South America’s glaciers. Though the law was created nominally to protect the glaciers, in fact, as Constanza argues, “most glaciers in our country would remain unprotected, and that, dangerously, what the legislation actually did was legalise and enable their destruction”—in this case, by mining companies. Their campaign has achieved significant success: their analysis of the law has the backing not just of environmental groups, but also of the Chilean Supreme Court, and currently the bill appears to be going nowhere. “I think one of the things we’ve learnt about is self-empowerment,” says Constanza, “and losing this fear is so important because as every person in the world starts doing it, we liberate ourselves bit by bit. In organisational terms, it’s also about realising and valuing that, yes—there is power in numbers.”

Voices of Latin America will be published by Latin America Bureau and Practical Action Publishing in October 2018. It will also be accompanied by a website on which we will gather additional material both during the project and once the book is published, including video and audio. If you want to help make these voices heard and feel you have something to contribute—whether material, research, ideas or translation skills—please get in touch with Tom Gatehouse.

Notes

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the position of ILAS or the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Latin America Bureau (LAB) is an independent charitable organisation based in London providing news, analysis and information on Latin America, its people, politics and society.

Recent Comments