By Giuliana Borea (Newcastle University)

The works of Rember Yahuarcani, Brus Rubio and Harry Pinedo/Inin Metsa were already displayed at the Art Exchange Gallery. With Covid safety protocols in place, the exhibition Place-making, World-making: Three Indigenous Amazonian Artists was to open in the UK in January 2021, but then came the second lockdown. It was painful witnessing the many projects that were affected, at least for those who tried to follow the government’s instructions. But the will to keep making things happen opened up possibilities of discovering other ways of doing things and research, of connecting and interacting with others, and of creating accessible materials and experiences. Jess Twyman, the gallery’s director, and I, the exhibition curator, quickly redefined the exhibition as an online show, learning how to do this as we went.

This exhibition was part of the Amazonart Project under a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellowship of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme from 2019 to 2021, hosted by the University of Essex’s Department of Sociology. The project’s aim was to explore the aesthetical and political dimensions of indigenous Amazonian contemporary artists as they enter global art circuits, and to produce new curatorial narratives through a collaborative methodology with indigenous artists. It included fieldwork in Lima and the Amazon, an exhibition in the UK as an arena for collaboration and research, as well as participation in academic events. I travelled to the Shipibo community of San Francisco in January 2020. It was where I had done my first anthropological fieldwork 20 years earlier, and I was glad to be back. My plan was to return to the Amazon in April. I was also happy working at a university in a much-needed physical academic space, different from home and my role as the mother of two children. But then Covid hit, globally redefining our lifetimes as pre-Covid and under Covid. Travel, in-person encounters, and hugs had to stop.

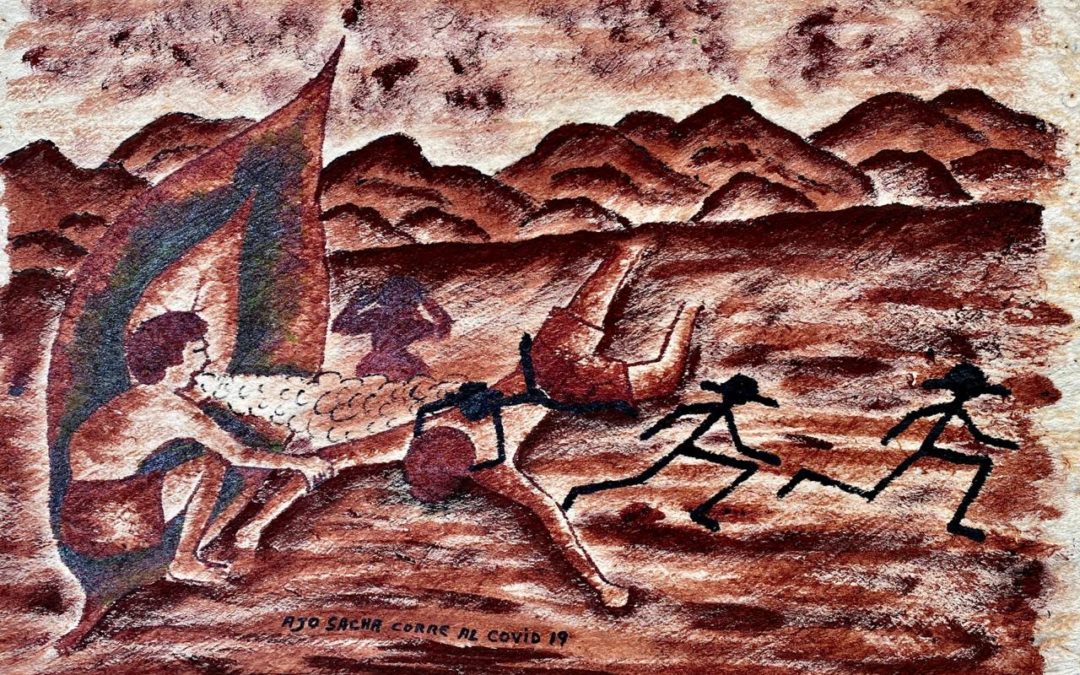

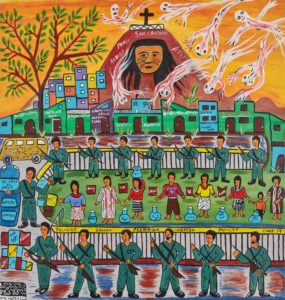

Many research projects and funding changed their focus to tackle the pandemic. Many indigenous artists decided to report on what was happening in their homelands, creating awareness and channelling help. Some approached and reflected on this situation through their work, social media postings and activism. Through Amazonart I worked with Rember Yahuarcani, Santiago Yahuarcani and Harry Pinedo to put together the project HERE: Fighting Covid-19 and Inequalities for a small grant from the University of York. Rember and I, who were already expanding our collaboration from art-based projects to co-authorship, curated the exhibition Ite, Neno, Here: Responses to Covid-19 at the Crisis Gallery in Lima. This was the first exhibition in a gallery on Peru’s mainstream art circuit to be curated by an indigenous person, opening up a space for Yahuarcani to reflect on indigenous curation and contributing to introducing indigenous Amazonian art into the gallery system. Featuring the work of Santiago Yahuarcani and Harry Pinedo/Inin Metsa, the exhibition explored how Amazonian people, particularly the Uitotos and Shipibos in Lima, lived, understood, and responded to the pandemic. Both artists materialised how their communities saw and understood Covid-19—the Uitotos, as a big monster and black silhouettes in Western clothes; and the Shipibos, as an airy being from the Yellow world, the world of diseases, highlighting the roles of their ancestors and plants in defeating Covid-19.

The making of the exhibition was the product of constant communication between the curators—an anthropologist and an artist—and the artists exhibiting their artwork via WhatsApp, email, Facebook, and Zoom, connecting the Amazonian town of Pebas, Lima and Norwich, where I live. Although I had given up on visiting the show in person due to the travel restrictions, a family emergency took me to Lima.

Curation was part of my previous anthropological work and research, but with Amazonart it became central. As travelling for fieldwork was cancelled, creating and particularly co-creating platforms—what George Marcus calls “para-sites”—as arenas for collaboration, experimentation, research and activism emerged strongly. The Amazonart website became another para-site, a web visualising the different assemblages that the project was producing amid the uncertainty.

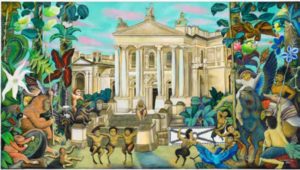

A month later Place-Making, World-Making opened. The exhibition featured Amazonian contemporary art in the UK and Europe, not with the recurring focus on shamanism, ayahuasca consumption, cosmology, or today’s ecological issues, but through different coordinates. With a serious approach to the works of different artists, I identified an interesting body of work addressing the practices of place-making and claims of belonging, and the strength of a generation of artists in their 30s. The approach took shape through various conversations with the artists and looking at and looking back together at their work. The works of Yahuarcani, Rubio and Pinedo in the exhibition highlighted issues of spatial politics and connections, migration, housing rights, cosmopolitanism, and indigenous current living conditions, as well as the impact of Covid. The show challenged the stereotypes that fix indigenous peoples in distant territories and narrow views of contemporary art.

The necessary online format of the exhibition pushed us to develop other strategies, such as a curatorial tour video and three videos in which each artist explained their art practice and perspectives of the artworld from their studios and homes. Produced by a team in Peru, who at the same time worked under the challenges of the pandemic, these videos were an important asset of the exhibition and found their own circulation. Strong social media publicity, online access, free downloadable catalogues in English and Spanish, and a rich public programme that allowed speakers and audiences from different parts of the world to come together, gave the exhibition a new type of circulation, impact, and afterlife.

But the artworks were in the UK—they had already cruzado el charco (literally “jumped the pond”, meaning they had travelled across the Atlantic)—and we wanted them to be seen directly. In Spain, the art spaces were already open, and the Latin American migrant grassroots organisation La Parcería, with its new art space, became interested in hosting the exhibition. Moving artworks was already difficult during the pandemic, but we also faced Brexit-related borders, customs, and paperwork. Our anxiety mounted. Finally, the exhibition opened in Madrid in July 2021, reaching a vast audience, with the artworks returning to Peru by the end of it. I have not yet returned there myself.

The restrictions on movement during the pandemic forced us all, individuals and institutions, communities and governments, to explore new ways of reaching out, of being there, of interacting, while living with the anxiety of the unknown, the spread of the virus, and death. Expanded fieldwork during the pandemic was carried out through hybrid forms across scenarios, strengthening collaborations with local teams, creating new platforms for research and interaction, and assembling different elements. But it was also carried out through, and with, researchers’ and collaborators’ layers of grief, resilience, and anxiety. Curation, in its widest sense of healing, was constantly needed in trying to navigate—or having to stop due to—our own and others’ losses and the difficulties to develop projects in the midst of a pandemic. Curation, as a specific cultural practice, became an arena for encounters and the hope of possibilities beyond the distance imposed, of greater experimentation in times of uncertainty, and of curating through curation.

Author

Giuliana Borea (@giuliana_borea) is Lecturer in Latin American Studies at Newcastle University and affiliated Lecturer in Anthropology at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the position of CLACS or the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Recent Comments