Illustration for learning toolkit. A’pe Buese – Aprender Brincando (São Paulo: Instituto Socioambiental, 2021), www.lindsaysekulowicz.com

By Elizabeth Chant (CLACS and University of Warwick)

Crossing both the northern and southern hemispheres and exhibiting a range of climates from tropical to desert, it is perhaps no surprise that Latin America is home to seven of the world’s seventeen megadiverse countries. Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Venezuela, four of these significant biodiversity hotspots, are each home to more than 5000 endemic plant species, and Mexico is estimated to be home to around 12% of the entire planet’s species, making Latin America a vital region for the study of issues such as habitat conservation and species distribution, as well as for bioprospecting. Protecting and understanding life in the region is also a critical component of the fight against climate change, especially since the Amazon rainforest, one of Latin America’s emblematic biodiverse habitats, is no longer a carbon sink, now emitting more carbon emissions than it absorbs.

These statistics show just how significant plants are in scientific scholarship on Latin America. Plants have historically been neglected in humanities scholarship, though. As Monica Gagliano, John C. Ryan, and Patrícia Viera have emphasised, animals have often taken centre stage (2017: vii). With the rise of fields such as environmental humanities in recent decades, plants have started to receive greater attention for their cultural and historical importance. Beyond the Columbian exchange, the ‘world-wide transfer of plants and animals begun in 1492 with Columbus’ arrival in the West Indies’ (Earle 2020: 35) that remains a key area of research, humanities scholarship in recent decades has been teasing out the connections and influences plants have had on material, literary and intellectual culture in Latin America, as well as how Indigenous knowledge of plants and plant life figures in human understanding of nature more broadly.

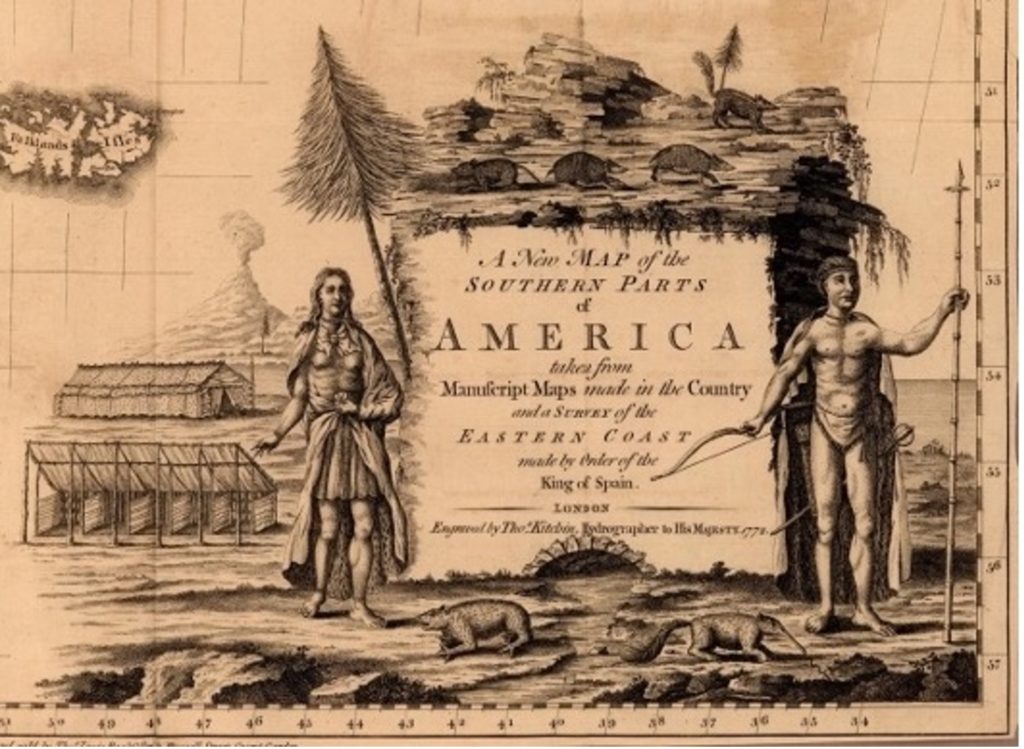

I came across a fascinating example in my own research when working on a 1774 map of Patagonia that featured an engraving of a tree, meant to be a Fitzroya (Fitzroya cupressoides) on the cartouche alongside other endemic fauna such as dwarf armadillos (Zaedyus pichiy) and Patagonian maras (Dolichotis patagonum). The map was published in tandem with A Description of Patagonia, an account written by English Jesuit Thomas Falkner that documented the region’s geography, Indigenous populations and animal and plant life with a view to facilitating English colonisation. This kind of cartouche imagery was common across European maps from this period, helping the reader to visualise the region in question. Engraved by Thomas Kitchin, the map uses the description to inform its depictions. But Falkner’s description of the Fitzroya in the text is notably vague: he never saw these trees with his own eyes, recording only what the Tehuelche told him about them: ‘It was not very particularly described to me; but I take it to be of the fir kind’ (Falkner 1774: 90). With only Falkner’s scant description as a guide, the cartouche trees do not resemble the Fitzroya, instead looking similar to a European larch. This brief instance shows how views of vegetal life in sources from the colonial period can evidence the overlaying of European ideals and knowledge onto foreign endemic species as artists, mapmakers, scientists and beyond attempted to marry descriptions of unfamiliar lifeforms with their existing botanical information. Kitchin most likely used a referent with which he was familiar, creating a hybrid species that merges features of both trees in the process. It also restates the importance of Indigenous agents and informants in the development of European botanical knowledge of the Americas.

Studying this example developed my interest in fields such as economic botany, botanical art, and traditional knowledge of plants in the Americas. In 2021 I took part in the Plant Humanities Digital Summer Program hosted online by Dumbarton Oaks in the U.S., which included training in areas such as the institutionalisation and development of botany as a field via the establishment of gardens such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and the aesthetics of plants in formats such as the plantation, landscape garden or walled garden. As a Visiting Fellow for 2021-2022 at CLACS, I wanted to learn more about the research going on in this area in the UK specifically in relation to Latin America, and so in June 2022 we invited experts to offer insights into their work in plant humanities at a workshop, including the practicalities of working with plants, how to approach vegetal collections, and how to uncover vegetal influences and narratives.

At the workshop, Lesley Wylie (University of Leicester) talked about the experience of writing her recent book, The Poetics of Plants in Spanish American Literature. Lesley explained the importance of looking at the libraries of the authors she studies, as this offered new insights into how their personal interest in botany and gardening influenced their fiction. Lesley revealed that she also found this reflected in residential spaces as well, noting, for example, the centrality of gardens in the houses of Pablo Neruda, whose work is examined in the monograph. We also heard from Luciana Martins (Birkbeck, University of London) and Lindsay Sekulowicz (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew/ University of Brighton) about their collaboration on the British Academy-funded project ‘Digital repatriation of biocultural collections: Rio Negro, Amazonia’, which disseminates information about the work of two European botanists in Brazil during the 19th century alongside contemporary Indigenous knowledge from this region. Lindsay, a practising artist, described their experience of hosting online plant drawing workshops in Brazil, and both scholars highlighted the importance of what they termed ‘learning to look’ at plants and biocultural collections comprising both plants and animals, which require us to pay attention to plants in a different way to how we might regard them in our daily lives.

We were also fortunate to hear from Iris Bachmann about the British Library’s extensive Americas collections, many of which include plant materials, and from Kristan M. Hanson about Dumbarton Oaks’ ongoing Plant Humanities Initiative and its Plant Humanities Lab, which includes in-depth, interactive narratives on a number of American plants including Peanut and Cacao.

The research and collections that we were able to showcase represent only a small sample of the exciting research going on in Latin American Plant Humanities in the UK and beyond. Some noteworthy current projects include the Endemic Plants of Chile project hosted by the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, and Microcosms: A Homage to Sacred Plants of the Americas, hosted at St. Lawrence University, which has compiled and exhibited three-dimensional image scans of plants considered sacred by Indigenous groups from across the Americas. The visual focus of many of these initiatives, bringing together techniques from across the arts and sciences, offer us new opportunities to ‘learn’ to look, understand and interpret as Luciana and Lindsay put it, and to re-evaluate the role of plants and vegetal life in this history and cultures of Latin America.

References

Earle, Rebecca. Feeding the People: The Politics of the Potato. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Falkner, Thomas. A Description of Patagonia. Edited by William Combe. Hereford: C. Pugh, 1774.

Gagliano, Monica, John C. Ryan, and Patrícia Vieira. ‘Introduction’. In The Language of Plants, edited by Monica Gagliano, John C. Ryan, and Patrícia Vieira, vii–xxxiv. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Author

Elizabeth Chant (@elizabeth_chant) is Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies (IMLR, School of Advanced Study, University of London), and assistant professor at the University of Warwick.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the position of CLACS or the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Recent Comments