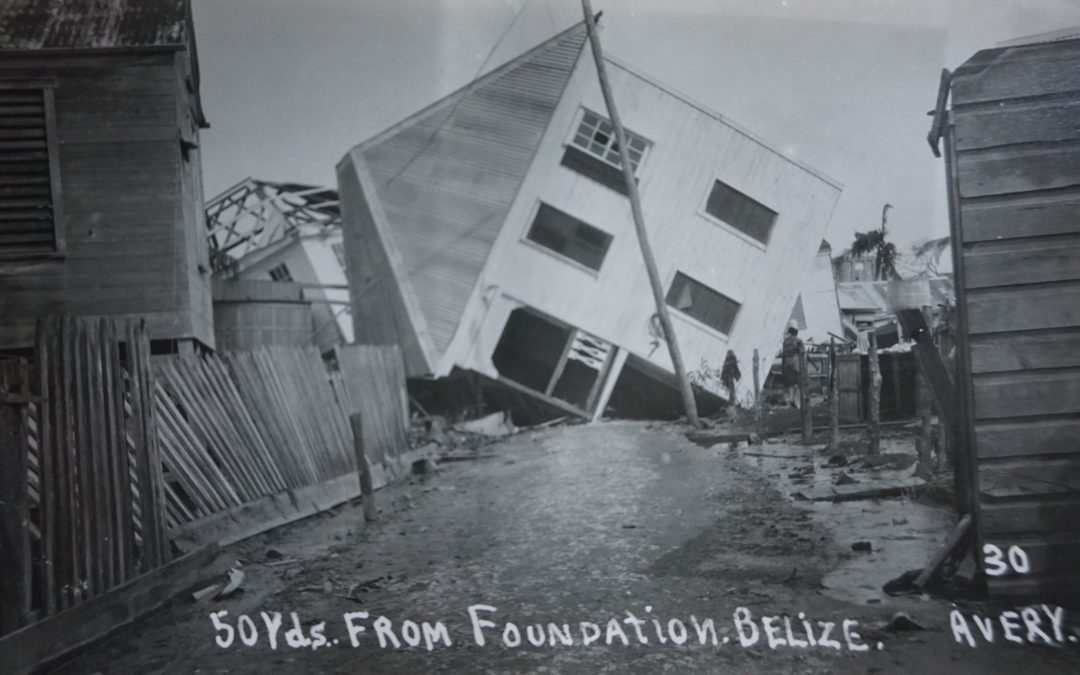

Credit: The National Archives (UK), CO 123/335/1,’Hurricane Disaster in Belize’, 1931.

By Oscar Webber (CLACS)

On 10 September 1934, Antonio Soberanis Gomez and several volunteers fed hundreds of hungry, mostly unemployed Belizeans for free. They offered this aid ostensibly because Belize (or British Honduras as it was known then), like many territories in the Caribbean, was suffering a deep economic crisis that the colonial government seemed both unable and unwilling to address. The date on which they offered this charity also made an important political point. 10 September had long been regarded as the colony’s birthday, it was a day typically marked by patriotic pageantry, but it also had far more recent and painful significance. Exactly three years earlier, the colony had been visited by a hurricane and tidal wave that killed at least 2,500 of the 15,000 population of the colony’s capital, Belize City. It caused the greatest devastation in the Yarborough neighbourhood where Gomez would later set up this free kitchen in 1934. This act of charity would also prove to be a starting point for a wider campaign of labour agitation against British colonial rule in Belize with Gomez, in the long run, coming to be regarded as the grandfather of Belizean nationalism.

As a historian of disasters in the British Caribbean, the hurricane, the British response to the disaster and its connection to the emergence of a broad labour movement in the colony intrigued me. In the eighteenth, nineteenth and very early twentieth century, disaster rarely, if ever, provoked the political agitation and contestation of white authority that colonial governments always feared it would. Instead, even during the time of slavery, most survivors of these events appear to have focused their efforts simply on trying to make it through the protracted periods of dearth that typically followed them.

As I began researching the topic, my interest in the disaster was further peaked a claim, made by a former president of the Belize Historical Society, Emory King, that the British Government knew about the hurricane in advance and chose to ignore warnings regarding its imminent arrival (Channel 5 Belize, ‘1931 Hurricane Myth Disputed’, 31 October 2000). He based his claim on a letter published by the Belizean E.E. Cain in his 1934 book Cyclone! The letter, sent by the colonial Government’s radio operator Donald Fairweather, noted that the colony had received warning of the hurricane on the 8th. Now further into my research, it is clear, King was, to a degree right, there was advance warning of the hurricane, but it was not entirely ignored.

On the 8th, Fairweather received notification that a hurricane would strike the colony’s southern towns and he immediately relayed that information via the telephone exchange (United States, National Archives Records Association, R8-84, Records of Foreign Service Posts, Belize, British Honduras, vol 99, Robert M. Ott to Secretary of State, 6 October 1931). The following day the harbourmaster was informed, and printed warnings were posted at Bridge Foot in the centre of Belize city. Later that day, he received updated information that the hurricane was actually heading directly for Belize City, he again took to the telephone exchange to make sure that the information was ‘disseminated as much as possible’.

Considering this information, one could argue that the people of Belize City had very little time to plan and prepare for the hurricane and telephone coverage was also very limited. I think it is also important to add that there was almost no generational memory of hurricanes in Belize; as of 1931, it had been at least a century since one had hit the colony. Survivors in 1931 recounted that many people who did receive the warning laughed it off. Together, these factors led to a serious underestimation of the threat posed by the hurricane and certainly played a role in increasing the resultant number of casualties.

That said, the colonial government did not entirely err on the side of caution. The celebrations planned for the 10th were not cancelled but altered. Some of the early morning parades were cancelled due to ongoing rain and the children due to participate were to receive their lunch indoors. The intensity of rain and wind rose throughout the day, peaking at around 132mph at 2:45, by 3:05 there was dead quiet. This brought many out onto the streets, especially children, who were then drawn down to the coast intrigued by the fact the sea had completely retreated. In the absence of generational memory of hurricanes, very few recognised this retreat for the warning sign that it was. The forty-foot wave that shortly followed decimated the low-lying Belize City, drowning thousands.

In his own recollections of the event, the then Governor John Burdon admitted publicly that he knew of the hurricane in advance and discussed it with other members of the government. It is likely we will never know the details of this discussion; one Belizean archivist suggested that it may have been purposely destroyed, but Burdon placed the blame squarely on ordinary Belizeans. He argued that the populace rejected the idea that Belize could be hit by a hurricane and took no precautions against them whilst ignoring the fact that he allowed the celebrations to go ahead, thus legitimising their lack of worry so far as it existed.

What makes Burdon’s shifting of the blame particularly striking is that, though he did not invent them, we know he personally placed great emphasis on the importance of the celebrations of the 10th. The celebrations themselves emerged in 1898. The date was chosen to commemorate the 1798 battle of St Georges Quay, where a supposedly racially diverse group of British colonists and enslaved peoples defended the colony against numerically superior Spanish forces. The middle class African-Caribbean people involved with confecting the holiday saw it as a means to encourage reflection on the benefits of racial harmony, in turn strengthening their own minority position sandwich between white elites and the black working class. Burdon clearly liked the premise but desired to take it in a far more pro-imperial direction. In his 1927 book A Brief Sketch of British Honduras he spun ‘a heroic Rule Britannia interpretation of 1798 that reinforced the myths of benign slavery and racial deference’ (Macpherson 2007: 85). In the wake of the hurricane, he also reaffirmed the role of the celebrations as a means to remind local population of the importance of loyalty to King and Empire.

It is in this context; we begin to see why Burdon may have been keen for the celebrations to go ahead. By 1931, the economic misery brought by the Wall Street crash was rippling across the Caribbean causing much intertwined racial and economic tension as ordinary people struggled for work. Belize was no exception and was already experiencing much of these issues as its mahogany industry entered what would become a near terminal decline. In advance of the 1931, celebrations, there was already a worry on the part of the government that the celebrations would not take place owing to a lack of enthusiasm on behalf of local merchants. The celebrations were an event that could reaffirm the ‘natural’ racial order of the colony precisely at a time when economic factors threatened to shatter it.

In Britain, the Colonial Office and the Treasury would go on to deliberate for years about a loan to the colony; when it did arrive, its terms excluded the working class. Conditions in the colony worsened significantly making Gomez’s actions in 1934 more significant. He did what the British colonial government never did; he provided free, unconditional relief to his fellow citizens and, in doing so, laid the groundwork for a labour movement that would provide a long-term challenge to the British colonial government. The failure of the Governor to appropriately warn the colony was also confidentially discussed by the local American consulate, who shocked by his mismanagement, arranged to privately receive their own warnings in future directly from the U.S. Meteorological Service.

There is still much to uncover about the hurricane. I am particularly interested in trying to unearth the roles played by the Black Cross Nurses Association and the Carib International Society. These were two black led political groups and I am keen to know more about their interactions with the colonial state and the wider populace over the course of the recovery effort. As it stands, the evidence of colonial neglect as it relates to the early warning the government received, is a powerful reminder of the role which humans play in creating disaster.

References

Macpherson, Anne. 2007. From Colony to Nation: Women Activists and the Gendering of Politics in Belize, 1912-82. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the CLACS Early Career Fellowship in Latin American and Caribbean Studies.

Author

Oscar Webber is CLACS Early Career Fellow at the Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, which is part of the Institute of Modern Languages Research at the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the position of CLACS or the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Recent Comments