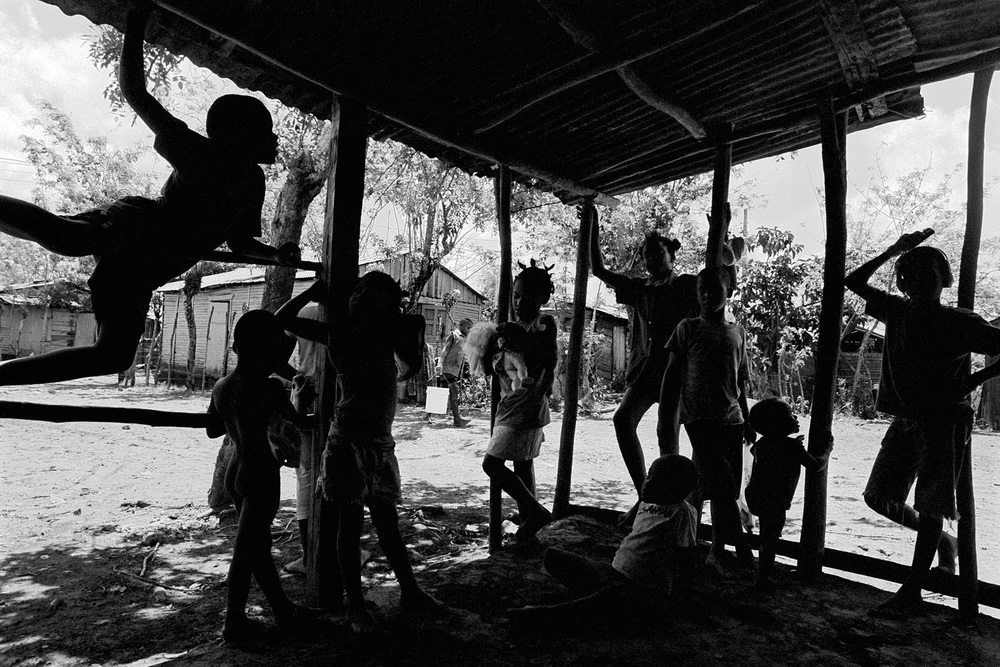

Nowhere People. A project on statelessness by the photographer Greg Constantine, available from www.nowherepeople.org

By Eve Hayes de Kalaf (CLACS)

Over the past three decades, a silent global revolution has been taking place which will have an impact on every living person on this planet. Far-reaching and transformative, digital identification systems have grown to become an integral component of everyday life.

Big tech companies, NGOs, legal specialists and governments are embracing the benefits of digital ID with considerable zeal. Their fundamental argument is that citizens, particularly the income poor, need to be correctly documented. Effective ID will help those included in these systems unlock their fundamental rights, thus facilitating access to essential state services such as healthcare, welfare and the financial sector.

Debates on identification measures, and the technologies that support them, are typically couched within a discourse of belonging, social inclusion and the universal right to a legal and, increasingly, digital identity. Now a central component in all development planning, access to social protection is wholly dependent on channelling assistance to those who hold the correct ID. Ambitiously, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are aiming to provide over one billion people with evidentiary proof of their legal existence by 2030.

Yet emerging research is providing some uncomfortable insights into the use and abuse of these modern-day identity-based development ‘solutions’. Earlier this year, Privacy International expressed concerns that digital identification is being used to discriminate against ethnic and religious minorities, noting:

“By virtue of their design, these systems inevitably exclude certain population groups from obtaining an ID and hence from accessing essential resources to which they are entitled.”

Although today large-scale efforts to document populations in Latin America are hailed a resounding success, historically identity/identities, race and constructs of belonging in the region were consistently (re)imagined, hierarchically structured and/or (mis)used for political and economic gain. Colonial regimes, for example, relied heavily on complex caste systems, racial categorisations and blanqueamiento (the process of whitening the race). They implemented these practices as a means to control, dominate and enslave populations. For centuries, Indigenous peoples, the Afro-descended and the income poor, especially women, were systematically excluded from the privileges of formal citizenship and treated as non-belongers in their country of birth.

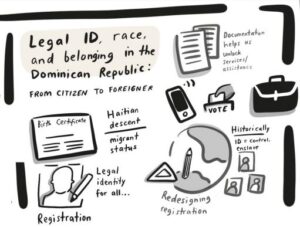

My new book ‘Legal Identity, Race and Belonging in the Dominican Republic: From Citizen to Foreigner’ highlights some of the limitations and problems with the en masse roll-out of identification practices. I illustrate how efforts to provide populations with proof of their legal existence resulted in the retroactive exclusion of hundreds of thousands of (largely) Haitian-descended citizens from the Dominican civil registry. These practices not only affected undocumented populations but also had a significant impact on persons who already held some form of state-issued national ID. While persons born to Haitian migrants had a legitimate claim to recognition as Dominicans, including the paperwork to prove this status, the authorities refused to provide them with a new biometric identification card. One woman told me about the problems she started encountering when registry officials refused to recognise the validity of her Dominican citizenship and instead retroactively (re)categorised her as a Haitian national:

“I told someone [waiting for registrations] that I didn’t want documents from immigration. What am I going to do with a document that’s meant for foreigners? What am I going to do if I’m not allowed to get my ID card? About two months ago, I went to buy a phone and they didn’t want to sell me one. They told me I couldn’t get a SIM card because I wasn’t registered [as a Dominican]. There are a lot of things I’ve wanted to do but can’t. I can’t get a good job with this card because they tell me I don’t appear in the system. I’m not allowed to vote.”

To understand more about the proliferation and impact of contemporary identity practices on constructs of citizenship and belonging, the Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at the School of Advanced Study, University of London, will be holding two-day conference on 23rd and 24th June. Organised in collaboration with the Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, ‘(Re)Imagining Belonging in Latin America and Beyond’ will tackle a number of themes related to identity, digital ID and citizenship rights.

Panel themes include sociohistorical examination of nation-building practices; challenges to legal definitions of status, particularly for migrant-descended and non-binary populations; analysis of the recent Windrush scandal in the Anglophone context and the BUMIDOM in the Francophone Caribbean; the impact of biometrics on the fundamental rights of the citizen; and an exploration of citizenship-stripping, statelessness and foreign-making practices in the region.

To identify further synergies, ‘(Re)Imagining Belonging in Latin America and Beyond’ will close with a global panel which will explore issues over access to citizenship around the world. Speakers will give papers on DNA testing as a bordering practice in Thailand, the use of mobile phones to encourage civil registrations in Ghana, biometric management and challenges to citizenship in Kenya as well as problems with the National Register of Citizens in India.

By linking regional issues concerning the exclusion and discrimination of migrant-descended groups with global measures designed to promote the inclusion of citizens, this conference will resonate with academic and non-academic audiences. It will help facilitate discussions on race and belonging, the legacies of slavery, forced labour and postcolonial identities in Latin America and beyond, particularly in relation to the bureaucratic organisation of populations and their lived experiences.

In the age of COVID-19, disputes over identity, access and rights are only set to intensify. Coronavirus passports, ID cards for the vaccinated and track and trace apps have the potential to not only seriously inhibit our ability to travel overseas but also to restrict freedom of movement within our own borders. Challenges over how citizens are identified, who is deemed eligible for inclusion onto ID systems and which groups should be given access to life-saving vaccines will inevitably lead to increased tensions in responses to the pandemic. It is time therefore for greater scrutiny over who are we including and who is being left out of this digital revolution.

Author

Eve Hayes de Kalaf (@EHayesdeKalaf) is Stipendiary Fellow at the Centre for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the position of CLACS or the School of Advanced Study, University of London.

This is a great and important piece. I am very much looking forward to the conference in June.