by Dr. Gibrán Cruz-Martínez, Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Latin American Studies

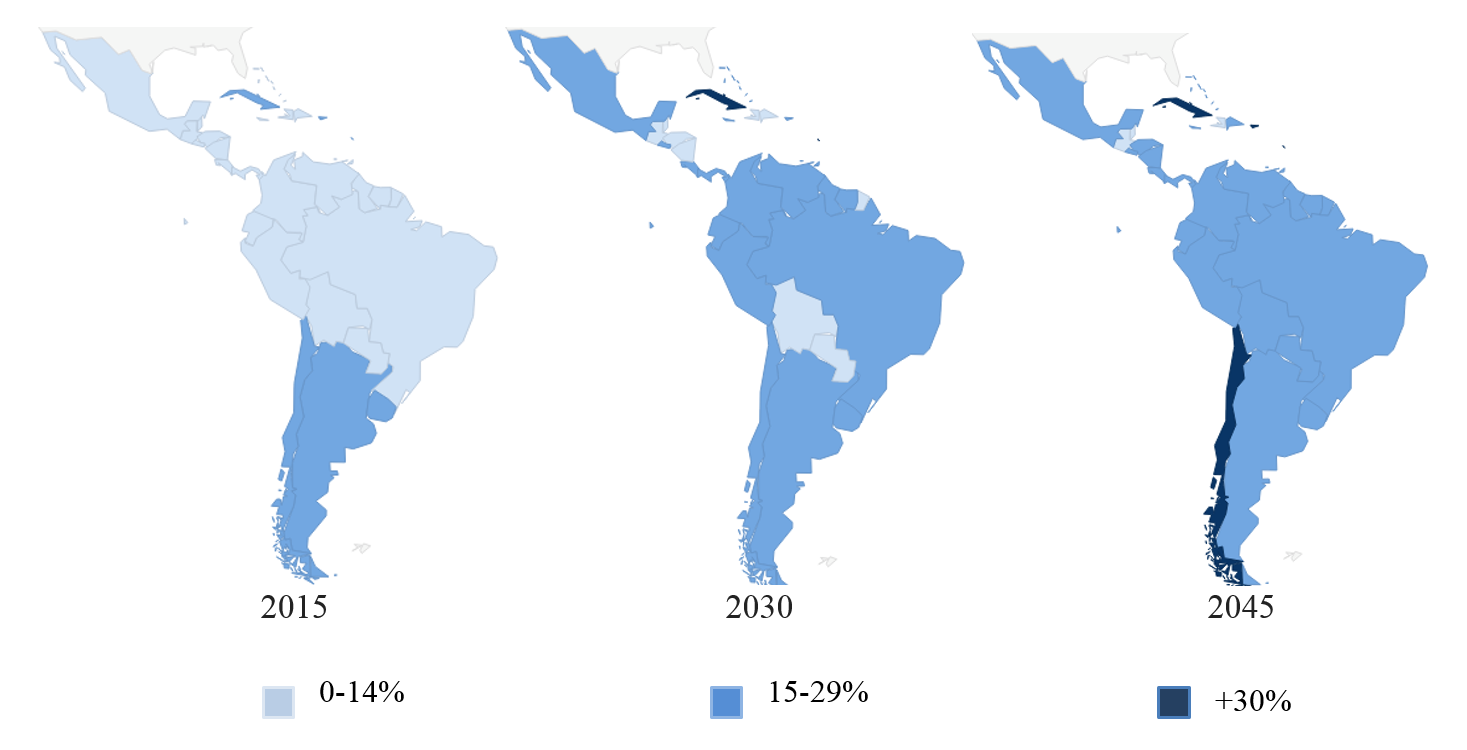

The world’s population is ageing, and Latin America and the Caribbean is no exception. By 2030, the number of older people – those over 60 – is expected to grow by 56 per cent (United Nations, 2015), and will outnumber children below 10 (HelpAge International, 2015a). Latin America and the Caribbean is expected to be the region with the fastest growth of this group (71 per cent increase), followed by Asia (66 per cent), Africa (64 per cent), Oceania (47 per cent), North America (41 per cent) and Europe (23 per cent) (United Nations, 2015).

Figure 1: Estimating the ratio of older-age population (60+) in 2015, 2030 and 2045, source: UNPD, 2015

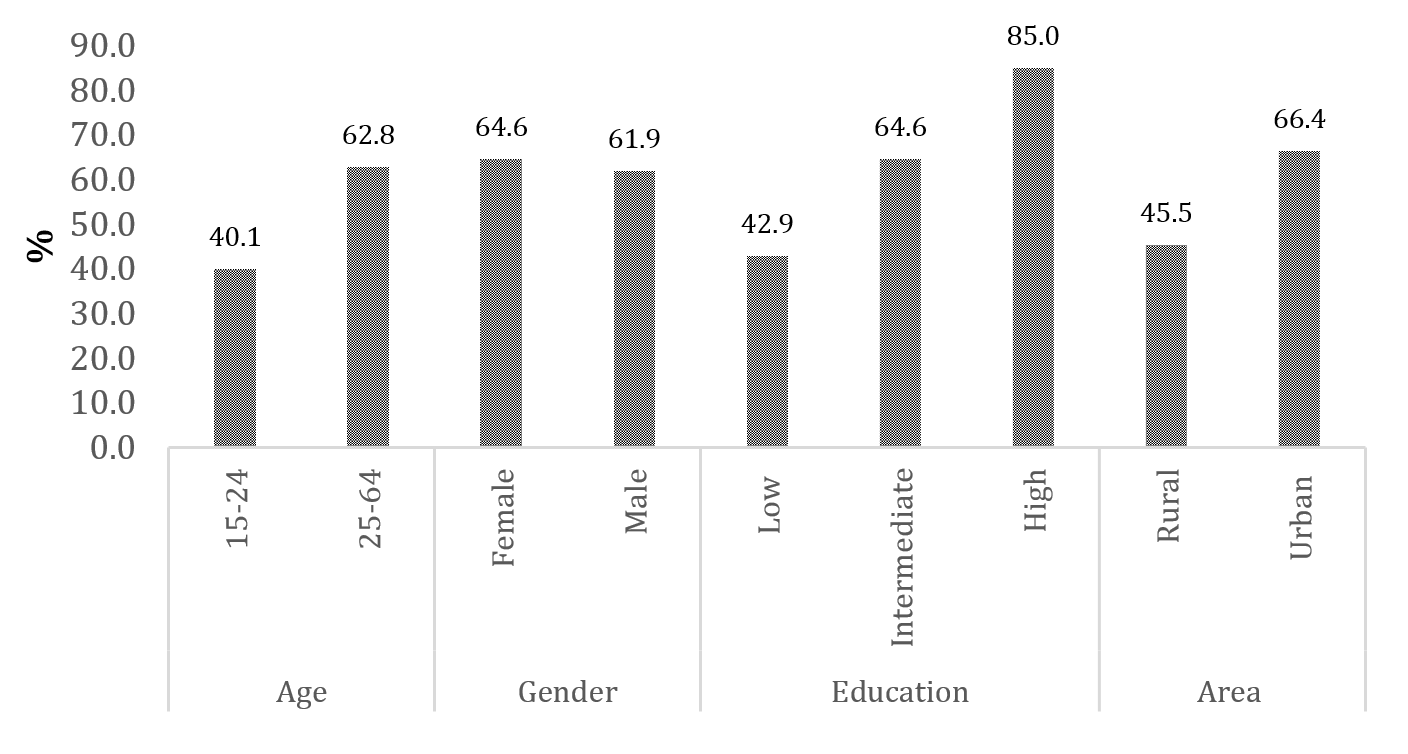

Ageing may bring wisdom and experience, but it also creates new social risks that need to be anticipated. According to the latest data from the Socioeconomic database on Latin America and the Caribbean, 57.7 per cent of salaried workers have the right to pensions when retired (CEDLAS and World Bank, 2016).[1] Therefore, almost half of the current workforce will not benefit from a contributory pension during retirement. If data is segmented by age, gender, level of education and area of residence we can examine the gaps in contributory-pension coverage.

As Figure 2 shows, there is a considerable gap in all categories, with gender the only possible exception. Workers aged 15-24, adults with a low level of education and residents in rural areas are the groups whose retirement is worst provided for. One possible explanation is that these groups work in more flexible and informal jobs, with less social security benefits than older generations, urban populations, and workers with over 13 years of formal education.

Figure 2: Share of salaried workers with right to pensions when retired by age, gender, education, and area, source: CEDLAS and World Bank, 2016, notes: SEDLAC (CEDLAS categorize level of education as low (0 to 8 years of formal education), intermediate (9 to 13 years), and high (more than 13). Author’s own calculations using the latest data for Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela.

Increasing the proportion of salaried workers contributing to a social security pension scheme is imperative. But is there any other alternative? What can governments do to guarantee the wellbeing of older people who are not set to benefit from a pension scheme? Universal non-contributory pensions – also known as social pensions – represent a viable option worthy of consideration.

Social pensions are non-contributory programmes that use benefits to bring the incomes of older people up to a societal minimum standard. Social pensions can be universal or targeted. Universal social pensions are available unconditionally to those who meet eligibility criteria of age and typically some form of residency. Targeted social pensions use additional targeting measures (e.g. assessment of means or assets) to identify the ‘truly deserving’. The main difference between social pensions and contributory pensions is that the latter are based in social-insurance schemes, with benefits derived from work or taxes and centred on redistribution throughout the life cycle. In Latin America and the Caribbean, workers in the formal sector are the main beneficiaries of contributory pensions, but the large segment of the population working in the informal sector is not covered.

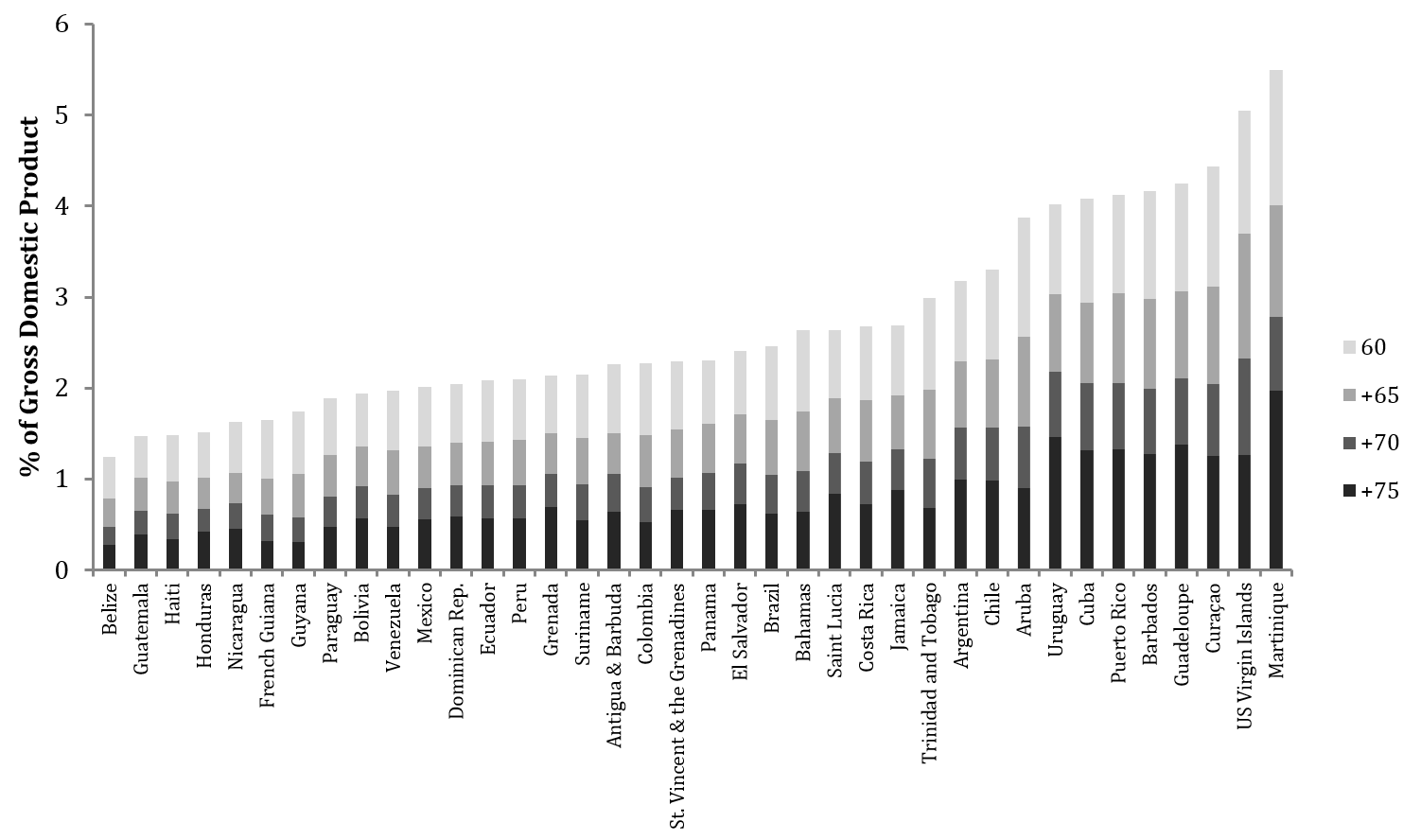

In countries with a low level of contributory pension coverage, a basic universal pension could guarantee income security and a basic social-protection floor for every older person. But how much would it cost to implement a basic universal social pension in the region? This will naturally vary according to the pension level – the value of the benefit – and coverage – the age of eligibility. Here I use four eligibility ages (60, 65, 70, 75) and one pension level (20 per cent of gross domestic product per capita)[2] to examine different scenarios. Data comes from the United Nations Population Division (UNPD, 2015) and is available for 38 countries. A modified model of Willmore’s (2007) formula is used, adding 5% of the total cost of transfers as administrative cost, previously proposed by Knox-Vydmanov (2011: 3).

As the results shown below reveal, all Central American countries would be able to finance a basic universal social pension with less than 0.7 per cent of their national GDP (age of eligibility 75). South American and Caribbean countries would need on average 0.6 and 0.8 per cent of their national GDP to fund a basic universal person for everyone over 75 years. The cost of a universal social pension in the total region varies from 0.3 to 2% GDP at 75+ coverage, from 0.5 to 2.8% GDP at 70+, from 0.8 to 4% GDP at 65+, and from 1.2 to 5.5% GDP at 60+. Unsurprisingly, the cost of a social pension rises as eligibility age decreases and pension level increases.

Figure 3: Cost of a basic universal pension equivalent to 20% of the GDP per capita in 38 Latin American and Caribbean countries, author’s calculations; source: UNPD, 2015

In Latin America and the Caribbean only four countries have implemented a basic universal social pension: Antigua, Bolivia, Guyana and Suriname (HelpAge International, 2015b; Shen & Williamson, 2006). For example, Bolivia introduced Renta Dignidad in 2008 to replace a cash transfer program created in 1997 (Bonosol). The eligibility age for Renta Dignidad is 60, and it currently has 869,808 beneficiaries, meaning around 88 per cent of those eligible (APS, 2016). The monthly income transfer is 270.83 bolivianos (US$ 39.83) for those who are not beneficiaries of the contributory pension scheme, and 216.67 bolivianos (US$ 31.86) for pensioners of the contributory scheme.[3] Most beneficiaries are women (53.4 per cent) and recipients of the contributory pension (83.3%).

The total value of transfers under Renta Dignidad in 2015 was equivalent to 1.2 per cent GDP.[4] The simple model used in this article estimates that a potential basic universal pension in Bolivia of 354.08 bolivianos (US$ 52.07)[5] for everyone over 60 would cost approximately 1.9 per cent GDP (including an estimated administrative cost). In Bolivia’s case the model appears to be presenting an accurate picture of costs.

There are many ways to finance basic universal social pensions. Bolivia, for example, funds Renta Dignidad mainly from taxes on fossil fuels (Mendizábal & Escobar, 2013), whereas Guyana uses budgetary allocations from central government (IMF, 2006). Among the possible alternatives for other regional governments are (1) increasing tax revenues by non-regressive methods (e.g. taxes on financial transactions, targeting the top 1%), (2) relocating public expenditure to social protection, and (3) improving the efficiency of expenditure (see Harris, 2013; Ortiz et al., 2015). There is no magic solution that fits all cases. Each country will have to examine its own reality and implement a unique mix of policies.

But overall this post has revealed that there are multiple options for financing and implementing social pensions throughout the region. The real question is whether there is the political will to make the necessary fiscal and monetary arrangements. The clock is ticking and the population is ageing rapidly. The time to act is now.

*Previous versions and analyses related to this article were prepared while the author was a Research Fellow in Social Protection at HelpAge International.

References and Notes

APS (2016). Estadísticas De La Renta Dignidad. Version of 30 April 2016: https://www.aps.gob.bo/estadisticas/Renta Dignidad/Estad%C3%ADsticas de la Renta Dignidad (Al 30 de Abril de 2016).pdf [accessed 11 June 2016].

CEDLAS, and World Bank (2016). Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean. http://sedlac.econo.unlp.edu.ar/eng/ [accessed 11 June 2016].

Harris, Elliott (2013). Financing Social Protection Floors: Considerations of Fiscal Space. International Sociel Security Review, 66(3-4), 111-143.

HelpAge International (2015a). Pension Watch. Social Protection in Older Age. http://www.pension-watch.net/ [accessed 11 June 2016].

HelpAge International (2015b). Pension-Watch Database. http://www.pension-watch.net/download/55129fc5749ec [accessed 11 June 2016].

IMF (2006). Guyana: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper Progress Report 2005. IMF Country Report, 06(364) https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2006/cr06364.pdf

[accessed 11 June 2016].

Knox-Vydmanov, Charles (2011). The Price of Income Security in Older Age: Cost of a Universal Pension in 50 Low and Middle-Income Countries. Pension watch briefing series, 2, HelpAge International.

Mendizábal, Joel, & Federico Escobar (2013). Redistribution of Wealth and Old Age Social Protection in Bolivia. Pension watch briefing series, 12 , HelpAge International.

Ortiz, Isabel, Matthew Cummins, & Kalaivani Karunanethy (2015). Fiscal Space for Social Protection. Options to Expand Social Investments in 187 Countries. Extension of Social Security Working Paper, 48, International Labour Organization.

Shen, Ce, & John B Williamson (2006). Does a Universal Non-Contributory Pension Scheme Make Sense for Rural China? Journal of Comparative Social Welfare, 22(2), 143-153.

United Nations (2015). World Population Ageing. New York: United Nations: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Highlights.pdf [accessed 11 June 2016].

UNPD (2015). World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision. http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ [accessed 11 June 2016].

Willmore, Larry (2007). Universal Pensions for Developing Countries. World Development, 35(1), 24-51.

World Bank (2016). World Data Bank. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx.

[1] Author’s own calculations using the latest data for Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay, Venezuela.

[2] These pension levels are ‘lab tests’ – arbitrarily assigned – and do not necessarily represent an adequate basic income for all countries. Median/average income, median/average salaries and median/average income poverty line could be examined as alternative options for pension levels.

[3] Author’s calculation using Renta Dignidad data from APS (2016). Conversion rates are accurate as of 11 June 2016.

[4] Author’s calculation using GDP data from the World Bank (2016), and Renta Dignidad data from APS (2016).

[5] Author’s calculation using GDP per capita data from the World Bank (2016). Conversion rates are accurate as of 11 June 2016.

Recent Comments