by Dr Amy Penfield, ILAS Stipendiary Fellow 2015-16

On the morning of Monday 7th December, I was greeted with news reports of the Venezuelan ruling socialist party’s (PSUV) landslide defeat in the previous day’s parliamentary elections, accompanied by images of jubilant crowds celebrating on the streets of Caracas. Hailed as the long-awaited end to Chavismo and of the divisive Bolivarian Revolution, one would be forgiven for taking the results to signify a change in government. Indeed, with the opposition alliance Democratic Unity Roundtable (Mesa de la Unidad – MUD) now holding a two-thirds ‘supermajority’ in the National Congress, they possess the power to make significant changes to government spending and legislation, as well as to potentially re-write the constitution and initiate a recall referendum against the current president, Nicolás Maduro. The election results were broadly reported as a response to widespread discontent with President Maduro’s administration and the severely debilitated economy.

Petro-citizenship and the lurking devil

Despite the outward appearance of a dramatic shake-up of parliamentary powers, as Tinker Salas and Silverman have noted in their analysis for The Nation (December 8th 2015), grievances over dubious democratic processes, food shortages, poor currency management, and rising crime rates often mask the true origins of Venezuela’s on-going and inherent instability: a dependency on oil. Tinker Salas and Silverman argue — as did Coronil in his classic study of the Venezuelan oil industry, The Magical State (1997) — that the Venezuelan economy has been ‘addicted to oil’ since the birth of its petroleum industry in 1908. All ensuing regimes, regardless of political ideology, are buttressed by the petro-dollars that make up the bulk of state revenues (currently accounting for 97% of export revenues), and are entirely at the mercy of its characteristically volatile price. Alongside illusions of ‘dazzling development projects that engender collective fantasies of progress’ (Coronil 1997: 5), the famously branded ‘devil’s excrement’ (el excremento del diablo) was found to be the shrouded begetter of political corruption, criminality and greed, a phenomenon more commonly known as the ‘resource curse’. These observations are as relevant today as in 1997, when Coronil’s book was first published, and reveal why a number of observers aren’t so optimistic about the opposition’s capacity to offer up remarkable remedies to widespread discontent amidst a backdrop of plummeting oil prices.

Aside from assisting in the illusions of state leaders, oil is also woven into processes of subject formation among citizens who harbour a sustained sense of entitlement to the benefits of oil wealth, a dynamic described by Coronil as an intimate relationship between the social body and the natural body of the nation. The late Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution was exemplary in bolstering this imaginary of the social-natural dyad through its endeavour to channel the nation’s oil wealth into endogenous development projects, free education and healthcare, and subsidised food for the entire population (i.e. not just the country’s elite).

Figure 2: A local ‘Mercal’ in a Venezuelan frontier town. This state-run chain of shops was set up under Chavez’s government, and provides subsidised food and household essentials for poor neighbourhoods. Photo by the author.

Oil is political, gasoline is personal

So, what does the future hold for these erstwhile beneficiaries of Venezuela’s prolific oil wealth? And what do the election results signify for those who might not have been celebrating the outcome so joyously? My own fieldwork in Venezuela between 2009 and 2011 explored indigenous people’s experiences of Bolivarian socialism and political inclusion, as one of the disenfranchised populations targeted for the petroleum-funded socialist initiatives. During this time, it became clear that abstractions of oil wealth for certain poor communities did not feature centrally in burgeoning notions of citizenship, nor to local-level comprehensions of rights to the ‘natural body’ of the nation. What became paramount in daily performances of citizenship was rather the ubiquitous derivative of oil — gasoline — which the entire population encounters daily as the tangible manifestation of oil and its omnipotence.

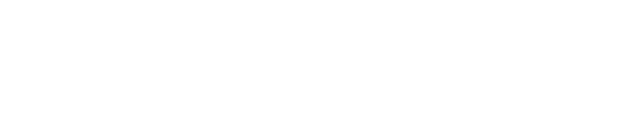

The political potency of gasoline in Venezuela is due in part to its extremely low price, the result of a subsidy introduced in the 1940s when Venezuela was emerging as one of the world’s main suppliers of oil (currently, for example, 120 litres of gasoline can be bought for only US$0.01). Since the subsidy was introduced, Venezuelans have viewed cheap gasoline as a birth-right, perhaps even more so than the dispensation of petro-wealth in the form of national development and social provisioning. This is so much the case that it is difficult to imagine a successful attempt to raise the price of gasoline, even amidst regular threats to do so (see Miroff 2014; Baverstock and Strange 2014). Indeed, price hikes might very well be applied if it weren’t for the shadow of El Caracazo looming over any who dare take this fateful step.[1]

In a situation strikingly similar to the current hardships experienced in Venezuela today, falling oil prices in the 1980s led to an economic crisis and the subsequent decision to remedy this through increased gasoline prices under neoliberal reforms. The price adjustments brought about a wave of protests, riots, and a violent military crack-down on the 27th February 1989, known as El Caracazo, that left hundreds dead. It is clear to see, then, that whatever happens to the price of petroleum, and to the management of the somewhat abstract wealth accumulated from the sale of oil, subsidised gasoline is treated with great caution in recognition of its fundamental role in well-being and livelihood. It is, in this sense, a tangible manifestation of the nation’s oil wealth, and of Venezuelans’ rights to that wealth.

Gasoline-fuelled citizenship

Meanwhile, for the indigenous population of the country, daily encounters with gasoline are even more intimate and central to well-being, not least so for the Sanema, with whom I conducted anthropological fieldwork. For my hosts, the dual nature (the natural and social body) of the petro-state is experienced first and foremost in their direct and intimate interaction with huge quantities of subsidised gasoline, which is woven into every aspect of their practical and moral lives. This process of becoming ‘permeated with gasoline’, as it were, is related in no small part to the recent co-option of indigenous peoples into state building objectives.

The Venezuelan State’s interest in Amazonian territories began in the early 1970s with a plan to utilise the rich resources of southern regions — named the ‘Conquest of the South’ (la conquista del sur) — predominantly with the aim of building infrastructure that linked the Amazon regions to the rest of the country. This development of the south was a process that was later taken on by Chavez’s regime after his election in 1998, through an accelerated inclusion of indigenous peoples into the Bolivarian Revolution. For the first time in Venezuelan history, the indigenous population gained considerable recognition, most notably in changes to the 1999 Venezuelan Constitution which introduced a section devoted to native peoples, and which included clauses that espouse rights to collective land ownership, native education and health practices, and prior consultation for natural resource extraction in their territory. Notwithstanding this multi-ethnic vision, however, Chavez simultaneously directed attention to indigenous people’s history of exclusion and consequently promoted their equal incorporation into criollo-standardised [2] initiatives such as the hallmark communal councils, neighbourhood-run development projects that formed the backbone of Bolivarianism.

Figure 5: The outboard motor, one of the most common political gifts bestowed in Venezuelan Amazonia. Photo by the author.

From the perspective of my indigenous interlocutors, gifts and the direct supply of funds for these communal council projects figure prominently in descriptions of their motivations for migrating northwards, embarking on regular trips to the cities, and participating in political activities. The Bolivarian Revolution played a central role in accelerating regular and extended movements in Amazonia due to gifts of outboard motors and other machinery, profuse political events in the cities, and frequent paperwork errands. This process of political inclusion thus resulted in a new rapid and regular mobility that was facilitated by their newly obtained gasoline-guzzling outboard motors, which in turn required large and regular supplies of evanescent gasoline. Exacerbating this process was the government mandated monthly cupo (quota) of gasoline supplied to each indigenous community, an endowment that sustained their dependence on gasoline-run machinery, which again impelled them to regularly travel to the cities in order to procure the quota. We can see how such circular movements to the cities are self-perpetuating since one literally needs gasoline to get gasoline. Indigenous peoples, then, were swiftly embedded in a circulatory system of citizenship and dependency through gasoline.

Holding steady amidst change

It is easy to see that even amidst rhetorical powers of oil and the ever-looming threat that its volatile price ultimately determines (or indeed homogenises) the fate of political regimes; the price of gasoline, on the other hand, remains far more constant, and much more reliable. Cheap petrol has endured both neoliberal and socialist regimes. For the time being, then, many Venezuelans’ sense of citizenship remains sufficiently stable despite the ostensible overhaul in political power within the National Assembly.

So, while Venezuelan elites might view themselves as ‘stewards of oil wealth’ (see Tinker Salas and Silverman 2015), the country’s poor and indigenous populations channel their rights and citizenship through a more prosaic materialisation of the petro-state: gasoline. Hence, we might do best to look for a solution to Venezuela’s ‘addiction to oil’ in the more mundane daily encounters with this valuable energy source.

Figure 6: Indigenous community travelling to the city in their gasoline-powered canoe. One man wears a jackets proclaiming “Indigenous socialist warrior at your service!” Photo by the author.

Notes:

[1] Others have suggested that Maduro fears raising the price of gasoline, as it would have knock on effect for many other products (see Hetland 2015).

[2] Criollo is the local term used for non-indigenous Venezuelans or people of mixed heritage.

References cited:

Baverstock, A. and Strange, H. (2014). “Venezuelans fume as Government signals end to ‘free’ petrol” http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/10617632/Venezuelans-fume-as-government-signals-end-to-free-petrol.html

Coronil, F. (1997). The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Hetland, G (2015). “The End of Chavismo? Why Venezuela’s Ruling Party Lost Big, and What Comes Next.” http://www.thenation.com/article/the-end-of-chavismo-why-venezuelas-ruling-party-lost-big-and-what-comes-next/

Miroff, N. (2014). “Venezuela nears end of the road for gasoline subsidy.” http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/27/venezuela-petrol-subsidies-cheap-gas.

Tinker Salas, M and Silverman, V (2015) “’Democracy, as usual,’ in Venezuela.” http://www.thenation.com/article/democracy-as-usual-in-venezuela/

Recent Comments