by Dr Niall Geraghty, ILAS Stipendiary Fellow 2015

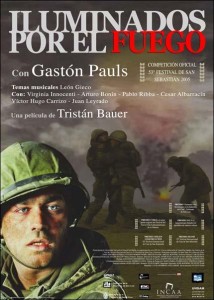

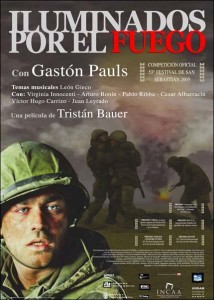

On the 4th of November 2015, the Argentine Embassy in London organised a screening of Tristán Bauer’s semi-fictional film of the Falklands-Malvinas conflict, Iluminados por el fuego [Enlightened by Fire] (2005). Present was Edgardo Esteban, author of the memoir on which the film is based, who introduced the film and took part in a discussion panel following the screening.[1] Also in attendance were several ex-servicemen from the UK who had served during the Falklands-Malvinas conflict and who participated throughout the discussion. Having had the opportunity to listen to the unique responses of those who participated in the conflict itself, I felt that perhaps now was an appropriate time to reconsider the film’s significance for those who, like myself, have no direct experience or memory of the conflict whatsoever.

On the 4th of November 2015, the Argentine Embassy in London organised a screening of Tristán Bauer’s semi-fictional film of the Falklands-Malvinas conflict, Iluminados por el fuego [Enlightened by Fire] (2005). Present was Edgardo Esteban, author of the memoir on which the film is based, who introduced the film and took part in a discussion panel following the screening.[1] Also in attendance were several ex-servicemen from the UK who had served during the Falklands-Malvinas conflict and who participated throughout the discussion. Having had the opportunity to listen to the unique responses of those who participated in the conflict itself, I felt that perhaps now was an appropriate time to reconsider the film’s significance for those who, like myself, have no direct experience or memory of the conflict whatsoever.

Iluminados por el fuego follows the character Esteban Leguizamón in the days following his friend Alberto Vargas’s attempted (and ultimately successful) suicide attempt. Both men had served together during the Falklands-Malvinas war and the re-emergence of Alberto in Esteban’s life brings back powerful memories of the conflict. Indeed, the film’s narrative is largely composed of flashbacks which recount Esteban and Alberto’s experiences during the war, interspersed with scenes from the present where Esteban and Alberto’s partner, Marta, accompany Alberto until his eventual death. The film concludes with Esteban’s return to the islands.

The film features the popular actor Gastón Pauls in the starring role and proved particularly successful, garnering many awards on the international festival circuit. However, in its narrative and its style, the film can seem a little too familiar. The problem is perhaps that, for an audience with no direct experience of the Falklands-Malvinas conflict, Iluminados por el fuego exists in a rather saturated field and consistently draws upon the familiar motifs of the war film genre. It would appear that, as Bernard McGuirk laments in his analysis, the film demonstrates that the ‘tropes of the war film are, in the end, but few. As are the modes of depicting the plight of returned veterans on the street’ (2007: 271).

Indeed, even the film’s inclusion of the ‘notorious practice of the estaqueo, a horrific brand of punishment in which soldiers were staked to the wet ground for hours at a time, very often in sub-zero temperatures’ (Maguire, Forthcoming), all too readily creates a link to José Hernández’s El gaucho Martín Fierro (1872). The central character in Hernández’s poem is, like the characters in Bauer’s film, a conscript abused by his military superiors and estaquiado while fighting for the patria on a contested frontier. The danger that emerges from this type of overfamiliarity is twofold: first, it may appear that the portrayal of the conflict relies on cliché; and second, that the ‘deployment of cliché […] widespread in war writing’ frequently obscures ‘its subject, concealing it from view rather than illuminating it’ (2011: 140), as Catherine McLoughlin argues in her comprehensive study of the literature of war.

It is inescapable, however, that the veterans present at the screening in the Argentine Embassy praised the verisimilitude of both the film’s battle scenes and its depiction of the suffering of those ex-combatants returned to civilian life. It would appear that for this audience, Iluminados por el fuego was all too familiar for a rather different reason. With this in mind, one is perhaps reminded of the words of Keith Douglas who, considering the poetry of the First World War as he participated in the fighting of the Second and sought to record his experiences in verse, would contend that:

“there is nothing new, from a soldier’s point of view, […] hell cannot be let loose twice: it was let loose once in the Great War and it is the same old hell now. The hardships, the pain and boredom; the behaviour of the living and the appearance of the dead, were so accurately described by the poets of the Great War that every day on the battlefields of the western desert – and no doubt on the Russian battlefields as well – their poems are illustrated.” (Cit. Piette 2007: 122)

Watching Iluminados por el fuego with this particular audience certainly led me to reconsider one important sequence of shots contained in the film as an attempt to reconcile these two interpretations of the film’s overly familiar feel: that the film runs the risk of becoming generic and clichéd, and that the film is genuinely reminiscent of a soldier’s lived experience.

Early in the film, following Esteban’s initial flashbacks to his departure from continental Argentina on his way to fight in the Falklands-Malvinas, the film’s linear narrative is interrupted by a sequence of shots drawn from contemporary news bulletins.

The sequence opens with General Galtieri addressing a vast crowd in the Plaza de Mayo at the outbreak of hostilities with his famous words ‘Si quieren venir, ¡que vengan!’ [‘If they want to come, let them come!’]. The sequence then moves through an unsurprising and very familiar series of rather stock images: an aircraft carrier with a Harrier jet taking off, artillery firing, images of the Argentine junta, of Margaret Thatcher, and other instantly recognisable scenes.

The sequence is, in and of itself, another instance of a rather overused technique to situate an audience in a particular time period. Moreover, in a film that seeks to avoid all ambiguity in its exegesis, it is rather unsurprising that the sequence is immediately absorbed into the film’s narrative: the archival footage is interspersed with three close-ups of Esteban’s face which reveal that he too is watching the same footage.

In the first of these shots (above) the camera faces Esteban directly and is backlit so that only the silhouette of his profile is visible. The camera pans round so that Esteban’s profile appears to move across the screen from right to left.

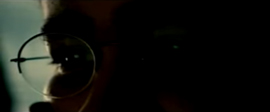

The second shot (above) is a perfect inversion of the first: Esteban’s profile moves from left to right across the screen, and this time the camera shoots from behind his head, so that the audience is watching the archival footage through Esteban’s glasses. In the final image (below), the camera returns to its original position and directly faces Esteban, signalling the end of this interruption in the narrative.

This sequence of shots represents the only moment in the film when the distance between audience and character is eliminated and they occupy the same subject position. Yet, if the sequence constitutes a moment of closeness between the audience and Esteban, it equally pushes them apart. For the audience with no direct experience of the war, these images essentially constitute the visual memory of the conflict. For Esteban, however, they may well be familiar, but they cannot constitute a visual representation of the war as he remembers it. Therefore, this sequence of shots actually marks the point at which the audience and Esteban essentially interchange subject positions: Esteban reviews the very matter from which collective memory of the conflict is constructed (but of which he is less familiar because when they were first transmitted he was fighting on the islands); just as the audience will subsequently view the images from his personal memory which are alien to them (as they have been excluded from that same collective memory). And the visualisation and incorporation of this alien memory into the collective memory was, of course, Bauer’s original intention while making the film.

As is now well established, following the defeat in the Falklands-Malvinas war, the Argentine combatants were subject to a strict pacto de silencio [pact of silence] which prevented them from ever speaking of their experiences on the island. It is in response to this omission from the historical record that Bauer made his film. As he has stated:

“I had to film the hidden defeat of the Malvinas: the failure of the military and the human tragedy that has been kept quiet. We Argentines have been converted into accomplices in covering up and hiding a reality about which we wanted to know nothing.” (Cit. McGuirk 2007: 269)

It is for this reason that McGuirk comments that ‘Iluminados por el fuego was to seek some balance in revisiting substantially the 1982 conflict and in coming to terms with a complex, conflict-torn and unresolved present’ (2007: 268). That this situation still continues today, and the important contribution made by the film, is emphasised when one recalls that it was only this year that the abuse of Argentine conscripts at the hands of their superiors was confirmed following the release of some 700 military documents related to the war (BBC 24/09/2015, BBC 14/09/2015).

In discussing cliché, Anne Carson argues that ‘[w]e resort to cliché because it’s easier than trying to make up something new. Implicit in it is the question: Don’t we already know what we think about this? Don’t we have a formula we use for this?’ (2008: 178). In the case of Iluminados por el fuego, however, it would appear that cliché is employed to a rather different end. Where the incorporation of archive footage certainly serves to remind the viewer of what we already think we know of the conflict, Bauer, in fact, mobilizes a series of clichéd tropes and images to expose to the audience that the formula they use to interpret the conflict is incorrect. Cliché becomes the very means through which the historical record is corrected. The over familiar and clichéd narrative ultimately encourages the viewer to reassess the war and consider it with others where the human cost and tragedy of armed conflict are at the forefront of collective memory. And revealing the human side of the conflict was precisely the task which Edgardo Esteban stated was an important motivation for writing his memoir from the outset. In this regard, the film is undoubtedly a faithful adaptation of the original text.

[1]. The panel was organised and chaired by Professor Bernard McGuirk (University of Nottingham) and featured Stuart Urban (Director and writer of the movie, An Ungentlemanly Act, 1992), Jeremy McTeague (Communications Executive, Falklands-Malvinas veteran, and author of ‘Who Cares About the Enemy?’ 2009), Tessa Morrison (Institute of Modern Languages Research), and myself, in dialogue with Edgardo Esteban. The present article is a revised version of the comments I made during the discussion.

Bibliography:

BBC News, ‘Argentine Conscript Speaks of Falklands Abuse by Superiors’, (24/09/2015) <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-34335103> [Accessed 11/11/2015]

———, ‘Argentine Falklands War Troops Tortured by their Own Side’, (14/09/2015) <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-34252025> [Accessed 11/11/2015]

Carson, Anne, ‘Variations on the Right to Remain Silent’, A Public Space, 7 (2008), 179-87

Maguire, Geoffrey, ‘Between Victims and Veterans: Remembering the Malvinas and Framing Nationalism in Julio Cardoso’s Locos de la bandera (2004) and Tristán Bauer’s Iluminados por el fuego (2005)’, in La Guerre de Malouines: Trente Ans Après ed. by Michael Parsons and Diana Quattrocchi-Woisson. (Forthcoming)

McGuirk, Bernard, Falklands-Malvinas: An Unfinished Business (Seattle: New Ventures, 2007)

McLoughlin, Catherine Mary, Authoring War: The Literary Representation of War from the Iliad to Iraq (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011)

McTeague, Jeremy, ‘Who Cares About the Enemy?’, in Hors de Combat: The Falklands-Malvinas Conflict in Retrospect, ed. by Diego F. Garcia Quiroga and Mike Seear. (Nottingham: Critical, Cultural and Communications Press, 2009), pp. 53-61

Piette, Adam, ‘Keith Douglas and the Poetry of the Second World War’, in The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century English Poetry, ed. by Neil Corcoran. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), pp. 117-30

Recent Comments