by Dr Luis Pérez-Simon, Co-Director, Centre for Integrated Caribbean Research, Institute of Latin American Studies

It is a historical fact that Cuba has always punched above its weight in matters economic, political and cultural, especially starting in the latter part of the 20th century. What may be less evident is that in the last quarter century it has done so diplomatically, and that the Catholic Church has staunchly accompanied it along the way. In fact, the Church has been a lifeline for Revolutionary Cuba since even before Cuba was revolutionary.

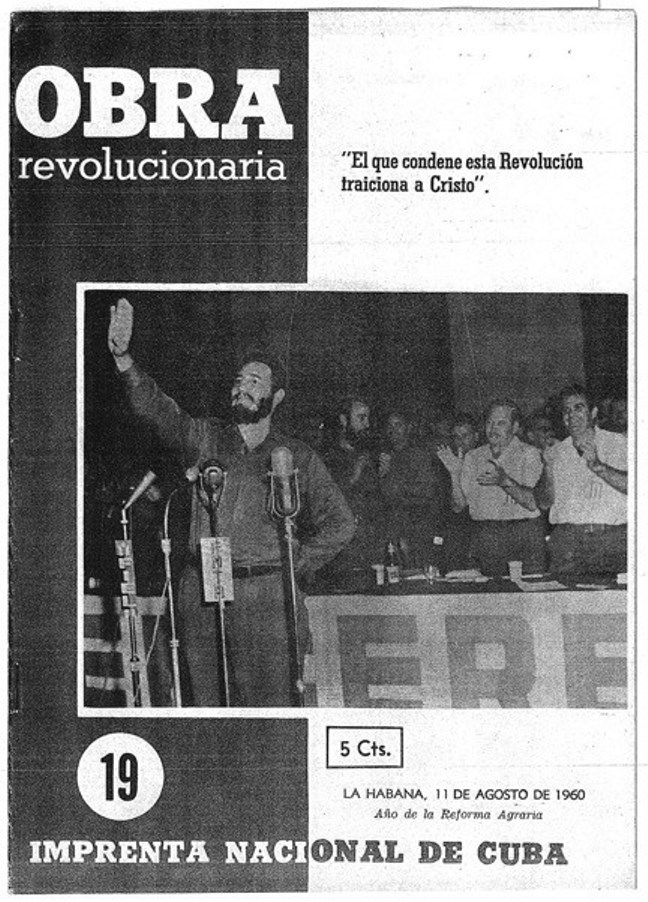

On August 1, 1953 security forces arrested Fidel Castro, six days after he had led an attack on the Moncada military barracks in Santiago de Cuba. However, he had not been captured. He had turned himself in. His surrender had been negotiated and orchestrated by Santiago de Cuba’s archbishop Mgsr. Enrique Pérez Serrantes, who also personally guaranteed his safety [1].

And although the Church’s fortunes in Cuba have risen and fallen since 1959 [2], its influence on the centre of power and on rebel ideology has been constant. Besides the obvious connection to Fidel and Raul Castro [3], traces of Catholic doctrine can be found in the socio-political Hombre Nuevo Socialista paradigm, the version of Marxism-Leninism that Cuba fomented in earnest throughout Latin America in the 1960’s and 70’s as part of its political internationalism, and the very idea behind the medical brigades launched in 1963 as part of its support for anti-colonial struggles and now forming the back bone of Cuba’s socio-economic humanitarian internationalism [4].

If the Castro regime sought to legitimise its nascent Revolution and expand its ideological reach, in part, by co-opting Catholic Liberation Theology in the 1970’s, it may yet do so nearly sixty years after the fact —and perhaps prolong it’s reach— by embracing Pope Francis’s ‘Reconciliation Strategy’ for the Americas.

Having reached an ideological and tactical dead-end with military incursions in Africa, Asia and Latin America, Cuba has had much more political success with humanitarian and medical missions in the developing world. Indeed, they have succeeded in fostering international good-will and support while helping to shore up the Cuban economy by providing health and education support internationally: the nearly 600,000 medical missions to over 158 countries have had a direct impact on more than 2 million patients, and its literacy campaign has been exported to more than 28 countries with hundreds of thousands of people being taught to read and write [5]. Beyond the recognition and gratitude of those countries directly impacted by these missions, other international actors –such as the Vatican [6]– have offered their support for what has become the single most resounding diplomatic success of the Revolution.

The moral and political capital gained from this internationalist humanitarian aid has proven invaluable for the Cuban State. On the one hand, it has contributed in no small measure to a consolidation of support for an end to the US. Economic Embargo [7], likewise fomenting calls for the re-inclusion of Cuba into regional institutions such as the Organization of American States and the Inter-American Development Bank. On the other, it has also had a direct impact on its very relationship with the United States. And has been widely reported, the Vatican was the fulcrum of the rapprochement negotiations.

The beginning of this latest collaboration between the Cuban state and the Vatican can be traced to 1998. The juncture of a heavy hurricane season [8], a re-elected Clinton administration [9], and the first papal visit to the island [10] provided the right mix of international good will, of American willingness to spend some hard-earned domestic political capital, and the emergence of a trustworthy and impartial intermediary in the form of the Vatican.

Though the process has been slow, it has been able to overcome several seemingly insurmountable obstacles, namely the transition from Fidel to Raul Castro as head of government and the Cuban Five-Alan Gross imbroglio. Indeed, it has been the steady support and encouragement by the Vatican that allowed both parties to capitalize on these very challenges to eventually reach a diplomatic understanding. Just as the arrest of the Cuban Five froze any collaboration with the Clinton Administration, the arrest of Alan Gross hindered any Obama initiative at moments when relations had begun to improve. Pope Benedict XVI’s 2012 visit to Cuba gave both parties new impetus in their gradual rapprochement. This followed a major overhaul of Cuba’s economic and social model by Raúl Castro [11], and foreshadowed the 2012 Policy shift toward reconciliation with Cuba initiated by the recently re-elected Obama administration [12].

Although normalization will take some time, this moderate pace will benefit both countries. Cuba will be able to ease into a global economy from which it had been excluded while doing its best to remain socialist, whereas the US will be able to advance its overall Latin American policy goals in a climate of international respect and collaboration. Pope Francis’ upcoming visit to both Cuba and the United States will serve as a further – and very real – bridge between the two countries. And the Vatican’s diplomatic and political influence will only grow in Cuba and in the rest of Latin America.

Endnotes

[1] A summary execution –likely by firing squad in the very Moncada barracks– would have been a likely scenario if Castro had been captured straight away. He remained at large long enough for the prelate to become personally involved. Additionally, in El hombre que no quiso matar a Fidel Castro, its author claims to have been ordered to poison Castro, an order which he refused to carry out in part due to his catholic beliefs (see p. 18-19).

[2] Although the Church sought to maintain its influence by offering a ‘third way’ between opposing ideologies, it was quickly sidelined once the Revolution declared itself Marxis-Leninist. Within a few years, over two-thirds of all priests had been expelled or had fled the country (including Cuba’s first cardinal, Manuel Cardinal Arteaga y Betancourt) and over 400 religious schools had been shut down. It wasn’t until 1991 that Catholics were allowed to integrate the Cuban Communist Party, and only a year later was the Constitution changed to forbid discrimination based on religious affiliation.

[3] It is widely known that both Castro brothers attended a Jesuit school and that they had strong ties to Archbishop Pérez Serrantes. See F. Castro & I. Ramonet, My Life: a Spoken Autobiography.

[4] An interesting case for a revolution and an Hombre Nuevo based in Catholic principles is made by B. Kenrick in A Man from the Interior; the Cuban leader himself discusses at length the Revolution’s support for Liberation Theology in F. Castro, Fidel & Religion: Conversations with Frei Betto on Marxism & Liberation Theology.

[5] see Burke, ed. Health Travels: Cuban Health(care) On and Off the Island and Unesco, Adult and Youth Literacy: National, regional and global trends, 1985-2015.

[6] Msgr. Sanchez Sorondo, Chancellor of the Pontifical Academy of Science went so far as to praise Cuba’s medical and educational aid to Latin America, calling it “a gospel of work” during an international conference on globalization and development problems in 2010.

[7] The last major vote by the UN General Assembly condemning the US embargo, in 2013, had full the support of all 190 member countries save for two: the Unites States itself and Israel.

[8] The one-two-three punches of hurricanes Bonnie, Georges and Mitch devastated a large swath of the Caribbean and Central America. Cuba responded by sending medical and humanitarian missions to Honduras, Guatemala and Haiti.

[9] It appears that for the first time since Cuba became a socialist country, Washington addressed the fact that the ‘Cuban issue’ was getting in the way of a Latin American policy that served American interests. See W. LeogGrande & P. Kornbluh, Back Channel to Cuba.

[10] The only other Latin American country to have had visits from all three John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Francis is Brazil. For an insight into the cultural impact, ideological shifts, and political meaning of JPII’s visit see M. Vázquez Montalbán, Y Dios entró en La Habana.

[11] It must be noted that beyond expanding religious tolerance and equality in the island, the Vatican has been an integral part of Cuba’s entrepreneurial and business administration education having established the first MBA program since the Revolution.

[12] C. Parsons & M. Memoli, in “Obama aides discuss Vatican role in warming relations with Cuba”, LA Times, April 10, 2015, point to a Situation Room meeting where it was decided to take a two-prong approach in approaching Cuba, secretly.

Readers interested in pursuing this issue further may wish to read the following article (and others on the subject of religion in Cuba) in the dissident but leftish web publication, <a href = "http://www.havanatimes.org/?p=250" title = "The Havana Times"..